5 Days

Mardin & Southeastern Turkey

November 26, 2018

IST GNY

My mom’s best friend was hunched over the concrete floor. Her hands were holding the loops of a dirty plastic bag while my mom carefully scooped dark dirt — the color of dried blood — into the bag. She then took the sapling rose and placed it in the middle of this mess.

We were in the departures lobby of Urfa Airport. Our plane back to İstanbul was waiting just across security check, where guards stood by. These were the same guards that a moment ago said that certainly, no, you cannot bring a potted plant like that onto the plane; please package it inside your carry-on. This was why my mother and her friend, Binnur, were fussing over the rose.

We bought the rose midway in our trip through the southeastern region of Turkey. It blooms black, or rather a very deep purple, and my mother purchased it off the back of a docked boat in Halfeti. It reminded her of a soap opera she watched a few years back, which was also called by the same name Karagül. “Your grandmother can plant it in her garden back in İstanbul,” she told me.

Top to bottom, left to right Immediately on landing, we stopped for breakfast at Tatvera in Urfa; even though typical breakfasts in the region dictate liver for your first meal, we opted for a less adventurous start. Balıklı göl, or Abraham’s Pool, is a scared site for Muslims and Christians. In the nearby covered bazaars, yards and yards of intricate textiles adorn all the walls with merchants always ready to offer a good deal. A family sits along the edge of Abraham’s Pool. Many will buy fish food to feed the sacred carp here.

Never mind that the rose receives its color from the soil and not from anything inherit in its DNA. The southeastern region of Turkey, populated by the cities Mardin, Şanlıurfa, Gaziantep, Midyat, and more, has been home to many flowering roses of civilization: neolithic, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Ottoman, Persian, Greek, Roman, Armenian, Byzantine, Kurdish, Turkish, and others.

Each has taken to the soil in a vibrant parade of diverse foods, cultures, and practices. Though often overlooked by travelers because of a tumultuous past, Southeastern Turkey is now becoming internationally known. We had four days to explore this region with my mother, her two friends, and myself.

Clockwise The Mosque of Şirvani in Gaziantep (Antep) Olives come in a dizzying array of choices from raw and green to a deep oxidized black. The city center of Antep preserves many of the crooked streets and traditional Ottoman-Arabic architecture. Pistachios grow in abundance in the region with each seller insisting that their batch is the most delicious.

Day 1

Arrival

November 26

My mother’s friend’s daughter-in-law’s mother — Kumru — picked us up from the airport and whisked us away to breakfast. The flight was short from İstanbul to Urfa, but we had left early in the morning, and our stomachs were sorry for it. Kumru missed the breakfast spot a few times before we finally found it. After settling in, the table was covered with local specialties. Traditional breakfasts in the region often start with liver, though we forwent that dish.

Our table creaked under the weight of all the food. No matter where in Turkey, breakfast is a large meal. All of the food was spiced. Spice is inescapable in this region: and there is no reason why you would want to escape from it. The spices here provide heat without burn. They snuck themselves into the cheeses, breads, meats, vegetables, and olives on our table.

Our itinerary for the next few days was full, Kumru explained. My mother and her friend, Binnur, nodded as they broke off another piece from the loaf of flatbread. We would be exploring Şanlıurfa first. Known in the past as Edessa, the city is renowned for its religious attractions as well as being near one of the oldest known human settlements in the world, Göbekli Tepe. Then, Kumru continued, onward to Gaziantep, Mardin, Midyat, Halfeti, and smaller sites along the roads to each city.

I gave an incredulous glance to my mother, but a quick search on our phones left us even more lost. The sun was getting low. It was time to admit defeat for this excursion.

We finished breakfast and left to explore Şanlıurfa. The plan for this day was to visit the prehistoric site of Göbeklitepe, which was a fifteen minute drive outside the city center. Kumru began driving: left, right, two lefts, merge, change lanes, stop for directions, reverse, restart phone navigation, shout road names, veer into dirt path, repeat “this must be the right way” for the third time, and finally stop and ask for directions from a group of working men: “The museum and archaeological site are closed today,” one of the workers said. We did not believe him becuse his friend immediately said it was open. A little more back and forth between the pair left us thoroughly befuddled. I gave an incredulous glance to my mother, but a quick search on our phones left us even more lost. The sun was getting low. It was time to admit defeat for this excursion. We would do more research and go another day.

In the remaining hours of daylight during winter, we decided to explore the historic city center or Urfa instead.

Left to right A blacksmith handles the body of a kettle. In the bakırcılar çarşısı, or copper market, located in Şanlıurfa (Urfa), the din of metalworkers bounces from workshop to workshop.

Once inside old Urfa, I didn’t lose much time in picking up dusty pieces of tarnished and beaten copper. These would need to be re-tinned and cleaned “red” to expose the natural copper underneath the dust and history. My mother didn’t lose anytime buying bolts and bolts of jaunty velvets and breezy chiffons. We all bought scarves made from the local fabric kutnu, which is a silk-cotton blend woven into jewel-toned ikat-like weaves.

By evening we collapsed into the courtyard of the old city bazaar. Surrounded on all sides by stone arches, the server took our order for coffee. He asked us if we’d be interested in the local specialty, menengiç (in the local dialect) or menevis (in standard Turkish), and we ordered a cup for each of us. Kumru said her husband plans to grow pistachio trees soon in the nearby countryside, and we would all be party to the bounty. Pistachios are abundant in this region. The trees they grow on remind me of the almond trees in California, yet pistachio tree branches are more distorted, writhing toward the sun. They are used in almost every dish in the region. Our coffee would also have it sprinkled on top, the server informed us.

The coffee is made from crushed “wild” pistachios from the turpentine tree. These pistachios are then dried and roasted. The preparation and presentation are nearly identical to Turkish coffee but the flavor is more mellow and herbal with the lingering taste of resin. We took to the drink immediately: every day we would enjoy a cup for the remainder of our trip.

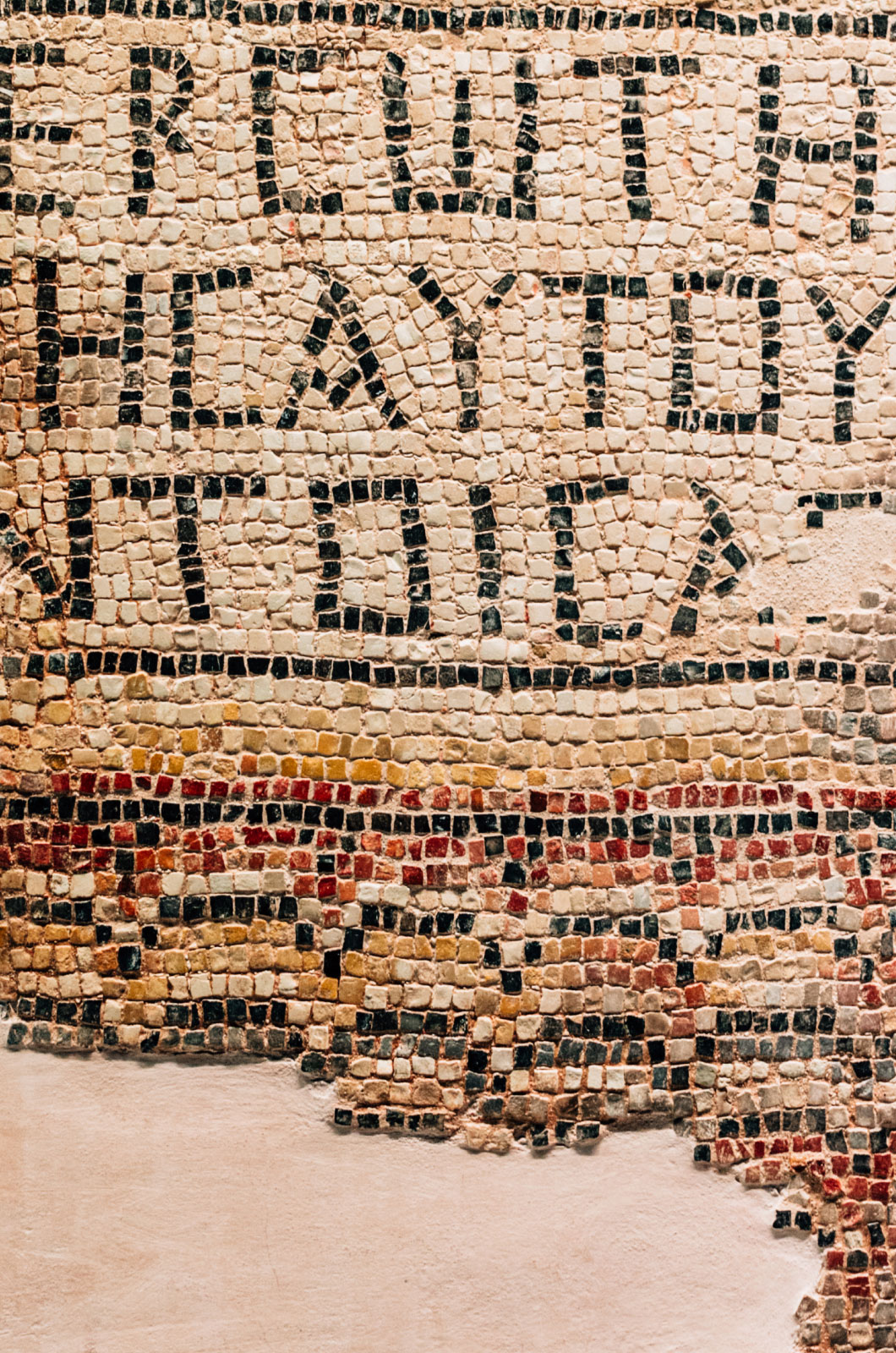

Top to bottom, left to right Along the Euphrates river in the area around Halfeti, parti-colored rocks rise from the water. A cup of the traditional menengiç coffee made from the seeds of the turpentine tree. A detail of Greco-Roman mosaics located in the Zeugma Museum. A sunken mosque has a single minaret rising from the waters of the Euphrates. A damn project completed in the 1990s submerged most of the riverside villages underwater leading to a rise in tourism to visit these curiosities. Areas along the waters are still farmed by locals. On the bow of touring boat, one can spend an afternoon seeing these sites. Many tours leave from new Halfeti including ones for foreign visitors. At one point well-above sea-level, the Rumkale fortress dates mostly from the Greco-Roman period, though it has been occupied intermittently until the Republican period of Turkey.

We ended our first day with a traditional feast with music called a “sir gece.” We sat on low cushions of a large stone hall on the top floor of an historic mansion set in the heart of the city of Urfa. Musicians lined up on one side: darbuka, kanun, voice, bağlama, violin, and davul. Dish after dish was brought to our table. The only issue was that the place was empty for most of the evening. In winter, tourism drops, Kumru explained. An unsold event became a private show for us. The emptiness made it easy for the loquacious lips of my travel companions to spill gallons of gossip between bites of çiğ köfte and swigs of powerful rakı.

Day 2

Halfeti

November 27

In the 1990s, the Turkish government began an ambitious plan to re-irrigate this region of Turkey. Historically, the “fertile crescent” encompassed a ring of civilizations with rich cities and abundant agriculture. But over centuries sands and rivers shifted and much of Southeastern Turkey was no longer arable. This project of building damns and new infrastructure is still ongoing and has brought much economic growth to the area.

It has also sunken countless historic treasures and ancient cities under the banner of progress. As many tour guides in the area lament: “we’ve sunken ten-thousand years of history for a few decades of progress.”

The city of Halfeti was one such place. It is most famous for a single minaret that pokes from above the waterline; below the water line is the mosque itself and the village it served. As the boat glided across the calm reservoir formed from the irrigation project, the captain would mumble anecdotes over the sound of Euro-pop hits and Turkish children’s march music. “That’s the İzmir march,” my mother said. The captain was a Kemalist.

We’ve sunken ten-thousand years of history for a few decades of progress.

The cliffs are parti-colored along Halfeti and very steep. I wonder how easy it could have been to inhabit that area: an Armenian cemetery clung like heavy snowfall on a steep roof and a Roman castle that once overlooked the area weeped piece by piece into the water below. Most of these structures are made from a porous sandstone that will dissolve once under water. Then the tour boats will move onto something else to entice visitors.

The road leading out of Halfeti is poorly maintained and winding. Kumru drives confidently through the fog, and our car whirls past the moss clinging to the shoulders of the road.

Many of the cliffs along the Euphrates have well-worn land that houses cemeteries dating back to the Roman period, as well as Armenian and other Christian burial sites. Older burial sites are often dug directly into the rock-surface.

My mother and her friend buy a kara (“black”) rose to take back to my grandmother’s garden in İstanbul. A soap opera bore the same name and ever since Halfeti has had brisk trade in rose saplings that we eagerly take back to the cities. My mother realizes that the iron in the soil gives the rose its color, but buys it anyways. One always has hope even when evidence clearly indicates otherwise.

Seeing Halfeti was bittersweet. The flooding of the region spurred major efforts by archeologies to rescue what they could. The end result is an impressive collection museums, archaeological sites, and cultural monuments that outshine most of what is found elsewhere in the world. On the other hand, whatever was not found has been lost underneath the waters of the damn-reservoirs. The Zeugma Mosaic Museum in Gaziantep, where we were headed next, contains hundreds of these works of Greco-Roman art.

Top to bottom, left to right Local grilled meats at Kebapçı Halil Usta in Gaziantep (Antep). Fermeneted yoghurt mixed with salt and water is frothed and served ice-cold in metal jugs; the drink is known as ayran. Tradition dictates that baklava came to the Ottoman court after the conquests of Egypt in the sixteenth century, when pastry chefs knowledgable in Arabic desserts were brought to the imperial palace, though this region perhaps had the delicacy much earlier. In Southeastern Turkey, some of the best baklava in the entire country is produced — and it is always filled with local pistachios. Cats roam freely in public and private spaces. This region in the Greco-Roman period was a wealthy trading center with local nobles outdoing each other in moasics of ornate color, material, and artistic merit. Most were rescued during the flooding of the rivers from damn-construction in the 1990s. The Zeugma Mosaic Museum houses some of the world’s most beautiful mosaics from the region that eclipse the ones found in elsewhere in the world.

We stopped at Kebapçı Halil Usta, a well-visited restaurant buzzing with locals and tourists. This place made a name for itself for it’s grilled meats, which come out one after the other served with “wet” salad — a speciality of the region — and freshly baked bread. But their baklava outshines it all: an outlandish amount of pistachios that spill out of buttered, infinitely stacked, paper thin sheets of dough. I asked the pastry chef to prepare a box for this evening, a box for my grandmother, and a few pieces for immediate consumption.

We are in Gaziantep, or Antep, now. During the battles that established the Turkish republic, many of the cities in this region received honorifics for their bravery. Urfa became Şanlıurfa. Maraş became Kahramanmaraş. Antep became Gaziantep. Cities like Halfeti were never renamed. Perhaps the inhabitants were cowards or the language ran out of words to express courage. We can now call it Batanhalfeti, or Sunken-Halfeti, to honor the progressive march of redevelopment.

I was glad to finally be out of the museum and in the old quarter of Antep: here the market was still buzzing and the din of copper being beaten was ringing nearby. We ordered pounds and pounds of pistachio: crushed, shelled, raw, roasted, whole, and salted. Our path wound around the shops that clung themselves closely to the main fortress of the city. My ears perked when I heard it was an excellent spot for buying old antiques.

Left to right In the ancient city of Dara near the Syrian border, enormous water cisterns, now empty, occupy the area. The strategic importantance of the city in the Roman period was substantial. Visitors can descend the steps to walk inside these cavernous water depots that are a marvel of Roman engineering. Grain is grown everywhere in the region much like it always has been in the Fertile Crescent. The damn projects, which have destroyed so many historic sites, provide irrigation and electricity to the region.

The sun was setting low and it was time for a cigarette break for some of us. Almost at the end of the bazaar, we spotted a dingy old building. The air was beginning to bite outside and once the cigarettes were finished, we walked inside. Inside we were dazzled: old oil lamps retrofitted with bulbs filled the space in golden light. This was a coffee-shop dating from the seventeenth century, or 1638 as the shop sign proclaimed. The site burned twice during the 1900s and was rebuilt. The shop was called “Tahmis,” which is a word for the place where coffee is ground. We ordered another round of menegiç and it was served with a medley of local roasted seeds. As we sat surrounded by uneven walls and delicious conversation, we began to settle into our new habits. Only a day-and-a-half into this trip, and my mother and friends felt like dowager queens of the countryside reclining on divans.

I saw a copper bowl earlier in the day that I couldn’t shake from my head. I said my goodbyes and left the coffee shop in a sudden hurry to make it back to the shop before it closed. The man was still there, and my mother, Kumru, and Binnur arrived in a fashion. It was time to haggle. My feeble attempts went to pot, but Kumru grabbed the items, slamming them on the table, nearly walking out with them, and insisted that we strike a midnight deal. Deal made. I managed to leave with a partial bounty, leaving the rest for another time.

Our second day ended and nightfall spread over Antep. We drove back to Urfa and put ourselves to bed.

Day 3

Mardin

November 28

Today we journeyed to Mardin, an historic city and absolute jewel in the crown of Southeastern Turkey. Before we departed for Mardin, we squeezed in a drive to Göbekli Tepe, the archeological site that has historians rethinking the development of civilization. The structures date from as early as 12,000 years ago, pre-dating almost, if not, all other known human settlements.

Near Kumru’s house was a lahmacun restaurant, Çulcuoğlu. Once we visited, we turned delirious desiring their food at all hours. Lahmacun is a paper thin pita dough that is spread on top with a thin paste of minced meat, tomato, onion, and spices. It’s a speciality from the Armenians of Eastern Anatolia, but has become popular in Turkey as a kind of pizza: a go-to item people from coast-to-coast eat as comfort food. Kumru promises we will eat here at some point.

Top to bottom, left to right Agriculture dominates the area around Dara. Local quarries provide much of the stone used in the architecture of Mardin, where local rules require it to be used in historic areas. Unlike most of Turkey where urban planning is often ignored, this rule is obeyed quite well by residents. Viewed from the Reyhani Kasri Hotel, a typical arabesque arch outlines the historic area of Mardin. Mardin contains churches and mosques from a variety of architectural periods. In Antep, Arabic-influence produced blended architectural styles like this protruding window above a dry goods store. Tahmis coffee in Antep claims nearly 400 years of operation. Over creaking floors and under wooden panels, one can enjoy local coffees served with their speciality nut-blend that includes roasted cannabis seeds.

We could not outpace the descent of the winter sun today: by the time we arrive in Mardin, it is dark. The outlines of the city are historic: jagged, uneven, but natural, and condensed. City planing was done by the breadth of a person and the pace of the foot. Our eyes light up as we see the variety of shops closing: künefe dessert, almond soap, pistachios (naturally), Jordan almonds, dusty copper, and so much more. “Tomorrow,” we tell ourselves.

To arrive in a new place by night is to see a place first as a dream and later as a reality when the sun rises. We’re tired, and we drop ourselves in our hotel room on the main thoroughfare. The view from the room is marvelous: I can’t tell what is out there because of the darkness. They say Mardin is a coastal city on account of the dark “sea” of farmland that surround it. At night, it looks like an inky ocean. Individual homes look like boats at sea.

Top to bottom, left to right The sloping hills of Mardin surround a castle citadel at the top. Antep’s copper markets are well-renowned in Turkey. The ceiling of the Ulu Mosque in Mardin is austere compared with the ornate interiors of Ottoman mosques in İstanbul. A door at the Ulu Mosque. A winding-uphill path near the historic postal station of Mardin, now used as a hotel.

Day 4

Monasteries, Dara, Hasankeyf, and Midyat

November 29

This is our last full day in Southeastern Turkey, and I manage by sheer will, to wake up and watch the sun flood the city of Mardin. The view turns from blue to pink to white as the sun mixes in with a thick cover of clouds. The city is built mostly of one type of stone, locally quarried. The land blends right into the buildings themselves since they are made of the same material. A light rain brightens the masonry, like spit hitting precious pebbles to bring out their color.

We hired a driver today to take us around the region. His Kurdish family has been living in the area for a long time, and he’s been giving tours to help bring attention to the beauties of this often overlooked destination within Turkey. The past few years of conflict have deterred most tourists, but the region has calmed down with increased tourism helping bring attention to the diversity of the region.

Left to right Shoes must be removed inside mosques like the Ulu Mosque in Mardin. In Beyazsuyu, fallen leaves linger into winter along a small river popular in summer with locals and visitors. During the colder months, it is an abandoned spot.

Our first stop is Kasımiye Medresesi. It was a crisp fifty degrees, and a crowd of people were just leaving the historic site. Like so many of the locals in the city, the workers who keep the medrese clean know as much about the history as our tour guide. Since most places are empty in the winter off-season, him and his friends took us around the building for a short tour, and indulged us with many, many photographs.

From there we were bound for the monasteries in the area. First, Deyrülzafaran Monastary, which lies very close to Mardin and was the seat of the Syriac patriarch for over six-hundred years until the Turkish Republic banned such things. It is still a functioning monastery though in diminished capacity. Tours start promptly here and move briskly. I had the feeling there was no desire to really invite people to tour the building: we’re a noisy distraction to the otherwise remote and tranquil beauty of this holy site. The members of the monastery create a special black tea spiced with an added herb called zafaran, which they grow on the property. Though what was shown to us was hardly enough to make even a few bags, and so they produce the tea mostly elsewhere in the region. It’s a strong black Assam as its base, much like regular Turkish tea, however the added spice gives it an aroma akin to cinnamon (it contains bits of cinnamon bark). Tea drinkers would be disappointed in it, but travelers, like myself, fell quite in love. A pound of it now sits on my shelf at home.

Top to bottom, left to right Side streets in Mardin often contain local merchants and markets crowded out from the popular tourist roads and should be visited. A man turns a corner toward the Ulu Mosque in Mardin, where one can easily jumble their footsteps along the old pathways. The library of the Latifiye Mosque is a quiet spot where aged locals talk quietly between the walls. The dome of the Latifiye Mosque. Nearby is the recently re-opened Protestant church. The past century saw years of bloody conflict between the Abrahamic religions that is only recently being reconciled. The Roman cistern at Dara.

We then visit the ancient city of Dara. Excavations began in 1986 and continue to this day. It was crowded for a winter weekday. A group of school students from the area were just leaving. Once the students left, Dara was deserted and it was only the four of us and our tour guide. The Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks, Arab caliphates, Artuqids, and Sassanids fought over ownership of this city for centuries. The city was finally destroyed by the thirteenth century and to this day is a small settlement.

And yet, the ruins contain a magnificent underground cistern from the Roman period, extensive tombs, and various stone buildings. It was a strategic and important area for a long period of time.

We continue driving to a place called Beyazsuyu. This is a river of no particular interest. The gushing, tumbling stream that people visit during the summer is popular for picnics. The ramshackle overgrowth of shoddily built pavilions and merchant stalls along the water’s edge makes it an altogether unenjoyable spot when winter empties it of its crowds.

Poplar trees lined the road from Mardin to Hasankeyf as we drove north. The city of Hasankeyf will be completely flooded and submerged in the next year or so as Turkey finishes a major damn project. Hasankeyf contains hundreds of cliff-side tombs from antiquity, and we had only a little time to visit the city. We stop for photos and to use the bathrooms.

Between all the cities we visit are wide soft landscapes of farmland. Short, crumbling walls of rocks demarcate property. The soil itself seems oddly rocky. Farming in this area seems rather difficult.

Mor Gabriel emerges around a turn. Mor is the Syriac word for saint. As we stand by waiting for the tour to begin, I wander to the edge of the property. An Orthodox priest walks by in black garb and a conical hat with a flat top. Monasteries are built from the local rock which is sandy in color and soft. It takes well to carving. Vine motifs of grape clusters are on many of the surfaces but I am not sure if vineyards still exist as industry in the area. There are architectural styles from many different cultures that somehow fuse together in a rather muted style as no surface is painted or colored.

We left the monastery and continued to Hasankeyf. This is another city besieged and owned by numerous empires. It lies on the Tigris river. It was odd visiting this city because in less than a few years the entire area will be submerged underwater. The Turkish government is finishing a damn project that will flood and cover thousands of years of history and displace an entire historic center. The city is overgrown: residents do not bother to upkeep something that will soon be gone. Monuments are either being left or relocated uphill. Peddlers are selling photo books of the city and lamenting the impending flood. My companions buy a few copies. I sit in the car after walking along one of the promenades. The chicken nearby is unaware of the distress. People are resigned to some fate that weighs down the air. I do not want to spend much more time here.

Elegiac Hasankeyf will soon be completely submerged under water from a nearby damn including the spot where these men gather to play backgammon. The Ministry of Culture is busily moving monuments of cultural significance above the pending flood waters though locals complain they are cutting corners when reconstructing them. Part of this negligence is caused by building methods no longer known by living architects and preservationists.

We ended our day in Midyat, another fortified citadel built upon a hill, much like Mardin. Unlike Mardin, though, the city has seen worse times and has not been able to take advantage of tourism as has Mardin. A famous soap opera in Turkey was filmed here — although when my mother and her friend explain any Turkish television series they always make it sound famous, as if they do not watch any other kind. The soap opera was filmed here, but it takes place in Mardin.

If you had limited time in this region, you could skip Midyat, though that recommendation may be precisely why the city is under-developed. The historic center is left in more decay while modernity has crept ungraciously onto buildings as satellite dishes, generic street lamps, and gaudily painted trash cans compete with the history left behind. In between this, you can still see the faint gasps of the restrained, warm stone architecture of older buildings.

Midyat is a center for silver in the region, though that reputation is a bit tarnished.

“All the silversmiths have left and gone to İstanbul,” the shop keeper tells us. The best ones are in the covered bazaars of İstanbul. This self-deprecating honesty is the speciality of merchants in Turkey. If you give the customer a sliver of vulnerability, you nurture friendship. Luckily Kumru is not gullible to such gimmicks. She has been my official bargainer. Where my American-gait immediately flags me, her aggressive bargaining saves the day. The three of them all buy matching silver jewelry as a memento of the trip. I sadly leave empty-handed. My luggage is already laden with copper.

It has been a long day and we were happy to be back in Mardin for dinner. The food in Southeastern Turkey is without a doubt some of the best in all of the country. Meals consist of a variety of small dips and preserves served at the start. These are mostly cold appetizers. Then there is soup and salad followed by the main course. We have been eating lamb and beef cooked until it falls off the bone.

Day 5

Departure

November 30

It’s been raining in Mardin all week long: in the narrow alleys the water floods the ground, and at the top of buildings the wind blows the umbrella out of my hand. I’m wrapped in cotton-silk “kutnu” scarves from local looms dyed in brilliant emerald, plum, and cream. When it’s the winter season, the weather may not be cooperative, but I feel like I have the city to myself.

Top to bottom, left to right A view from the upper-story of the historic post office of Mardin. Views from city center of Mardin diffuse into the vast agriculture lands. An antique copper bowl with lid was traditionally used to serve food. Quranic verses carved in stone at the Latifiye Mosque. Though partially reconstructed, the entrance portal of the Latifiye Mosque contains Turkic, Seljuk, and Arabic architectural styles typical of the pre-Ottoman period. Prayer beads made from semi-precious stones dangle in shop windows.

In the few hours before our flight leaves, we walk between more side streets. My travel companions are tired of seeing dirty, old copper, so I have no one to accompany me to those shops. I need to keep in mind that finding eccentric travel companions is a must. We skip shopping then and instead visit wonderfully restored historic buildings. Mosques, churches, homes, and imperial buildings are still in use today. Mardin is a working historic city. There is the central Ulu Mosque, which we visit first. We then stop into a twelfth-century mosque, Latifiye, and I take off my shoes to enter the prayer hall. It is empty inside, and I can hear the rain outside. Two gentleman are sitting in the library across the courtyard and wave for me to say hello. Across from the mosque is a Protestant church. It is not as prominent as the mosque, and was only recently re-opened. The congregation is small but is growing. My mother and the church keeper argue over religion with the phrase “with all due respect” passing between them repeatedly. Their arguments are as stubborn as the stones holding the church and mosque together. Much to both their surprises, the answers to religion have not been solved by either of them.

Mardin is well-known for almond soap, and we cannot leave without some of that. We buy more Jordan almonds. The sugared-almonds in Mardin are also well-known for a unique blue dye derived from what is called the Lahore tree, but I am unsure what that is in English. All I have written down in scratches in my notebook are the words “imlebbes — iodine? — lahor ağacından kök boya.” It dyes the sugar a pale periwinkle blue that borders on grey. The other coating is cinnamon. Both are delicious and we buy pounds of each.

We buy more tea and coffee, of course, and stop in the Covered Bazaar (Kayseriyye Bedesteni) for a few small trifles. We are at this point performing critical calculations on baggage allowances for our flight, divided by the carrying capacity of our backs and arms, multiplied by the cash we have left in our hands. The results are promising: buy more.

The winter weather has given Mardin a monotone color but the region itself is anything but monotone. I lost count of the civilizations that have inhabited, traded, fought, and co-existed in this region.

The rose is safely packed inside the carry-on. My mother and Binnur continue through security as I follow behind them.

I returned to İstanbul; my back cracked under the weight of dusty treasure. Every bag we brought back from our trip was full of delicious things. And shiny things. And old things. And unfamiliar things all ready to be wrapped and sent back home, much life myself. My mother planted the black rose in my grandmother's garden.

We had hardly settled back in when her friend called: anyone interested in visiting the hamams of Bursa?

Left to right Sustenance-farmed hills surrounding the Mor Gabriel Monastary. A well-worn path within the small village surrounding the ancient city of Dara.

Places

Where to Go

This 400-year old coffee shop roasts and prepares traditional Turkish coffee as well as the regional speciality coffee, menengiç, a resinous and thick herbal coffee made in a similar manner. Don’t leave without purchasing a bag of their famous roasted nut mix, which even contains cannibis seeds.

Kebapçı Halîl Usta

kebapcihalilusta.com.trTekel Caddesi

Öcükoğlu Sokak № 6

7500

Gaziantep

Turkey

Perhaps the best baklava of my life, but of course, the place is famous for it’s grilled meats, kebap. This region has something known as “spoon salad” (kaşık çorbası), which is a minced salad in a pomegranate-vinegar sauce. Make sure to add it to your order. In these institutions it is best to order the house specialities and ask them to pick their best dishes, rather than read a menu.

Çulcuoğlu

culcuoglurestaurant.comRecep Tayyip Erdoğan Bulvarı № 13

63300

Şanlıurfa

Turkey

Lahmacun anywhere in Southeastern Turkey, its rough birthplace, will be excellent. We particularly fell in love with this casual spot. Their lahmacun is paper thin with a fragile and crispy crust, perfectly spiced spread, and a no-nonsense focus on making these flatbreads. Ordering less than two a person would be criminal.

Zeugma Mosaic Museum

Zeugma Mozaik Müzesi

zeugma.org.tr

Hacı Sani Konukoğlu Bulvarı

27500

Gaziantep

Turkey

While the museum itself is rather dated and rab, the mosaics contained inside are some of the finest in the world. One can hardly imagine that these lined the rivers of the region in palatial homes that are now buried under water. The depth of color, complexity, and realism give a whole new perspective on the visual arts in the era of Ancivet Greece and Rome.

The city of Antakya is known for the famous dessert künefe. However, many places make this dessert in the region. This branch office in in the historic center of Mardin. The late hours means you can enjoy this sweet, syrupy dessert after dinner. It is more common in Turkey to go to a secondary spot to enjoy dessert after dinner rather than ordering at the same place where you ate your main meal. Many dessert shops specialize in only one dish.

Irmak Antik

Seller of the regional kutnu fabric, located inside the historic bazaar of Gaziantep. The fabric is a combination of silk and cotton hand-loomed using natural dyes.

Since 1914, Davut Selim has been selling regional sundries like sugared-almonds, menegiç, coffees, teas, and dried foods.

In a converted home of a once-wealthy family, this restaurant serves traditional fair including meze or appetizers from elongated copper spoons that each person passes until emptied. For dessert, aşk suyu, or lover’s water is a concoction of pomegranate, clove, ginger, lemon, cinnamon, and other spices and herbs. It’s efficacy cannot be confirmed or denied.

Our hotel was on the main street in the center of the historic city. Balcony rooms have sweeping views of the city and the plains while the upstairs serves a large breakfast. The hotel rooftop has 360-views of the city.

Kasımiye Medresesi

47100

Mardin

Turkey

Within the historic center of Mardin, Zinciriye is a classic example of a Muslim theological school.

Zinciriye Medresesi

47000

Mardin

Turkey

Within the historic center of Mardin, Zinciriye is a classic example of a Muslim theological school.

Abdüllatif Mosque (Latifiye Mosque)

47100

Mardin

Turkey

Dating from the fourteenth century, the mosques minaret was rebuilt in the nineteenth century. The hushed interior prayer hall is memorable for its austere and unadorned stone masonry, while locals will gather to gossip and relax in the courtyard.

Grand Mosque Ulu Camii

47100

Mardin

Turkey

The symbol of Mardin, built in the Artuqid period with a sliced domed structure. The minaret is best appreciated outside on approaching the building.

Marangozlar Kahvesi

47100

Mardin

Turkey

A small local coffeeshop in the heart of old town Mardin with an outdoor patio with sweeping views of the city and countryside. The interior is rustic and welcoming, and one can enjoy regional coffee specialties.

Mardin (Artuklu)

Turkey

Mardin is a hilltop citadel city with commanding views of the region. The historic center is beautiful preserved and has been continuously settled for over fifteen thousand years.

Mor Gabriel Monastary

47510

Midyat/Mardin

Turkey

Dating from the fourth century, it is the oldest working monastery for Syriac Orthodox Christians. Short guided tours are available (one cannot wander here). It is south of the city of Midyat.

Deyrülzafaran Monastery

47100

Mardin

Turkey

Near to Mardin, this Monastary is famous for its specialty tea. It was the center of the Syriac Patriarchate for nearly 700 years until the Turkish Republic outlawed working monasteries and religious centers. Short guided tours give you a glimpse into this building which is still a secularized but working monastery. There are attempts to move the Syriac patriarchate back to this site.

Dara

47100

Mardin

Turkey

Dara contains earlier Roman and Persian settlements as well as Christian structures. The underground cistern is the most spectacular part of this area and it is close to Mardin.

Midyat Guest House

Midyat Konuk Evi

47510

Midyat

Turkey

Restored a few years ago, this is the central historic building of Midyat and the site of a popular Turkish soap opera. The upper floors have a full view of the city.

Mardin Historic Post Office

47100

Mardin

Turkey

The old post office building was built by Armenian architect for the Şahtana Family in 1890. Later, it was used as a post office, and now it houses a hotel on the top floor.

Revaklı Çarşı

47100

Mardin

Turkey

The “porched bazaar” is directly behind the Reyhani Kasri Hotel. It is also known as the Cavalrymen or Middlemen Bazaar and dates to the seventeenth century. Coppersmiths, souvenir, and textile merchants can be found here.

The site of Göbekli Tepe is within fifteen minutes by car from Urfa, and yet it feels like stepping into another epoch. The discovery of this site has turned everything we know about religion, agriculture, and human civilization on its head. The site has settlements five thousand years older than Stonehenge leading archaeologists to speculate wildly about how we developed. It is best to visit Göbekli Tepe as early as the site opens: not only will you avoid the vans of tourists visiting, but the emptiness and solitude will enhance the effect of the stone structures. In the early morning, too, the mist of the night before rises up creating a curtain of fog around the area. The son of the original farmer who re-discovered the site that sits on his land is often found here, though he can only tell his tale in Turkish. Parking is done before the site, and one takes a short shuttle ride to area.

Food

What to Eat

Menengiç Coffee

kahvesi; a tree of the gum tree. Looks like juniper. Pistacia terebinthus, known commonly as terebinth and turpentine tree, is a species of Pistacia, native to Iran, and the Mediterranean region from the western regions of Morocco, and Portugal to Greece, western and southeast Turkey. In the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea – Syria, Lebanon – a similar species, Pistacia palaestina, fills the same ecological niche as this species and is also known as terebinth.

Çiğ Köfte

Çiğ köfte, literally raw meatballs, is a specialty of this region of Turkey. Raw, ground bead is kneeded vigrously with cracked wheat, spices, and tomatoe paste into meatballs. It is then served with a wedge of lemon and cold lettuce and eaten immediately. The dish has been outlawed in İstanbul for food safety reasons, but when prepared properly, it is as fresh and delicious as any raw beef dish you find in other cuisines. Look for places that specialize in this dish and who prepare it either in front of you or fresh. The taste is earthy and spicy and something you will become hooked on. A vegetarian version is made with lentils instead of beef and is nearly indisinguishable.

Kebap

Kebap is a blanket term covering a dizzying parade of various ground or whole meats that are grilled. These can be from lamb, beef, and other animals. Southweatern Turkey is well-known for their preperation of kebap especially in the areas of Urfa and Antep.

Lahmacun

This dish hailing from Armenain culinary tradition has always been popular. During mass-migration to İstanbul in the 1960s and 1970s, people from Southeastern Turkey took this recipe and began selling it in the major cities. It became so popular, that lahmacun is the unofficial symbol of Turkish “people’s cuisine.” It is not a classical Turkish dish but through mass culture has become one. The best lahmacun is prepared immediately on dough that is paer thin yet moist and soft on the innermost layer. A schmeer of minced beef, lamb, onion, tomatoe, and spices is spread across the top. It is then roasted for only a brief amount of time like a Neopolitan pizza.

There are endless ways of eating lahmacun. You can tear off chunks, roll it like a cigar, fold it in quarters or halves, cover it in fresh parsley, red onion, lemon juice, or simply eat it plain.

Künefe

A traditional Arabian dessert, künefe is popular throughout Turkey but is especially well-known in this area. Urfa peyniri (cheese) is heated at high temperatures in a shallow dish between two layers of shredded dough. When piping-hot, the mixture is dosed in simple syrup and covered in crushed pistachios. Ice-cold clotted cream, kaymak, is dolloped on top. It is an altogher marvelous way of bringin together hot, cold, sweet, crunchy, and creamy into one dish.

Pistachios

Turkey grows its best pistachios in this region. It is apparant: nearly every dish whether sweet or salty and every drink is flavored, sprinkled, cooked, and garnished wiht pistachios. They do not hold back. The best pistachios are vibrant, grassy-green, and you would do well to buy a few pounds so you never feel the pinch of indulging in them at home.

Language

Phrases

- Merhaba mehr-a-ba

- Hello

- Gün aydın guyn eye-din

- Good Morning

- İyi geceler ee ghe-je-ler

- Good Night

- Teşekkürler te-shek-cure-ler

- Thank you

- Evet e-vet

- Yes

- Hayır hi-ear

- No

- Pardon par-dohn

- Excuse me

- Özür dilerim oez-zuhr dee-ler-em

- Sorry

Written by Erol Ahmed

Photography by Erol Ahmed

Published June 2, 2019

Revised January 20, 2020